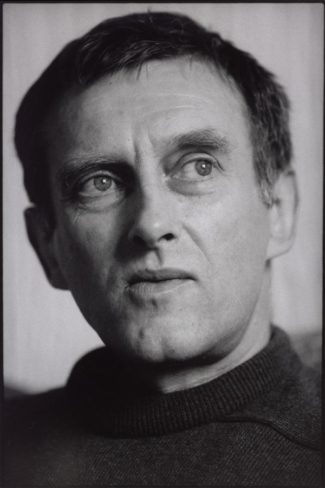

James Kelman eh? I am not going to add much to the short piece below, written for the New Statesman, in my late mid-twenties when I’d barely started a first novel called El Mundo, and when to have Kelman to engage in their pages felt like a sobering responsibility. A pleasure too, but the soberness got to me (rightly; Kelman is made an even more significant a writer by his latter neglect by the predictables) such that when I faxed it in, yes! I suddenly laughed out loud at my sending something with the words above as its conclusion; ‘siding’ instinctively, aesthetically, culturally and politically with something that would blow-up farcically three years later during the Booker Prize. What japes!

JK: It wasni even like a nightmare it was as if I was away somewhere else in my fucking heid

A phrase, which I associated with the stories but was from his not-so-great I thought plays, about being ‘away somewhere else in my fucking heid’ is one of those few golden lines from all time, endlessly ricocheting around my mind and experience. The full quote reads; Baird; ‘It wasni even like a nightmare it was as if I was away somewhere else in my fucking heid, away at some place inside it and I was just looking oot, the outside bits of my heid were shielding me form what was going oan, like it was a cave and therr wis me trapped inside- naw! no trapped, it wasni like that, I was just fucking inside, out of it aw, from what was going on roonaboot.’ (Hardie and Baird, 1990, p 178)

‘Away somewhere in my head‘, where else?

There’s also that line from Kelman’s introduction to these plays; ‘This is a time of punishment out there in the real world’, which reminds me of earlier lines from A Disaffection (198?, p 191);” Seriously: you’re just asking me seriously, if I’m a Marxist, in a school like this, in a society like this, at a moment in history like the present”. The explosion of vulgar brutalities by the Trussbomb (Sep 2022) puts all of us back into this kind of territory. Look on the upside; it’s the perfect occasion for a major reissue of all of Kelman’s works and a full on honest revival! He has found a publisher to begin that too (PM Press, Oakland California), as elucidated upon in the Salvage interview linked below. Kelman’s publishing story is also an object lesson in the impactfulness of a single smart editor operating within the publishing fatburger of the 1990/2000s.

Barely mentioned by me below are the lovely epiphanic stories in the collection like Margaret’s Away Somewhere and The Small Bird and the Young Person. If Kelman were not such a good line-by-line writer the magnificently confrontational pissed-offness and its preferred responses would not resonate anything like as much as they do… He is (seemingly) almost a writer from another age now; read him. Read him!

THE BURN

HARDIE AND BAIRD & OTHER PLAYS

James Kelman

April 1991

Guy Mannes-Abbott

In James Kelman’s fiction, people die alone, and lead lives in anticipation of it. In by the burn from the new collection, such a death is “a fucking racing certainty.” The short story is the perfect vehicle for Kelman’s relentlessly bald prose and street level screams. The complete absence of compromise in his fiction demands either negotiation or surrender.

In Naval History the narrator is asked “Are ye no still writing your wee stories with a working-class theme?” He responds: “its fucking realism I’m into.” Kelman’s politics have tended to be implicit in his celebratory re-working of the voices of Glasgow. Here there is a hardening of tone, in part, as a response to the collapse of welfare provision. Prefacing this collection of plays he warns; “this is a time of punishment out there in the real world.” These new collections of desperate individuals in “a permanent condition of being browned off with life”, make ever more explicit challenges.

In events in yer life, Derek returns to Glasgow for his mother’s funeral. When he asks an old friend if he is a Nationalist, he is told; “Christ … that’s hardly even a question nowadays I mean it’s to what extent.” In Pictures, a woman’s tears in a cinema signify sexual abuse, to the narrator. The idea of communication seems “incredible” to him: an effort both fruitless and farcical. The fact that “folk were getting chucked out on the streets these days; healthy or unhealthy”, is what makes such non-encounters unsettling.

This newly sharpened edge takes the form of a retired industrial saboteur in A situation. Wanting to “confess”, he approaches his dismal neighbour whose immediate concern is that, in the absence of home helps, “strangers were getting called in to wipe folks bums.’ Kelman appears no longer content just to mirror a state of “permanent separation.” There is a recognition that silences will have to be bridged. His attempts to echo this shift stylistically are clumsy. Metaphors can be blatantly Kafkaesque, and his women characters unexceptional.

It is an uncompromising call to arms

Kelman is at his best in the shorter works where he leaves out more than he puts in. Those spaces elevate his magnification of apparent inconsequence into dense prose. This epiphanic quality is exemplified in Margaret’s away somewhere, which makes her absence felt in just one page. Throughout the collection an exasperated repetition of words suggests creative frustration, and where phonetic opacity is pushed as far as it can go, as in the Hon, I sense exhaustion.

Much of the brilliance of his prose comes from the rendering of speech. But when he takes the same approach with dramatised voices in this collection of plays, it is a real disappointment. The exception is the title play about the Scottish Insurrection of 1820 in which Hardie and Baird were executed for High Treason. It is an uncompromising call to arms. Baird’s description of his state of mind in solitary confinement is a succinct summary of the Kelman character; “It wisni even like a nightmare it was as if I was away somewhere else in my fucking heid … out of it aw, from what was going on roonaboot.”

These are patchy collections which leave a sense of literal and philosophical stasis. Nevertheless, at his glorious best in by the burn, Kelman the stylist is unique. A man staggering through mud and rain on his way to a job interview is stunned to tears by the memory of his daughter’s accidental death. It’s opening sentence is an exquisite example of Kelman’s writing; “Fucking bogging mud man a swamp, an actual swamp, it was fucking a joke.”

…

Here is a pdf of the original: [coming]

I will add some critical pieces I have enjoyed below; starting with a new one by an old (Forest) friend;

.Existence is a guerilla campaign: an interview with James Kelman, by Rastko Novaković October 2022 in Salvage: https://salvage.zone/existence-is-a-guerilla-campaign-an-interview-with-james-kelman/

.‘I’ll die at the desk. So what. Where’s the coffee?’ short piece in The Guardian on writing lore by Kelman from August 2017: ‘At any one time I have around 150 stories in progress (plus essays, plays and novels).’

.’“A fine line can exist between elitism and racism,” he said. “On matters concerning language and culture, the distance can sometimes cease to exist altogether.”’ From ‘Scottish Writers are superior by far’… by Francisco Garcia in the New Statesman, March 2019, which rehearses the repulsive vulgarities displayed by the English not-even-literary establishment in 1994 most notably (re: Booker Prize); the kind that prides themselves on possessing a ‘well-stocked mind’ of untraceably thin gruel with a massive grating of patently insecure self-love on top. They would have said or say the same about oiks like William Blake and John Clare -as if they had ever read either or read Clare for instance like Anne Carson did with such wordly savour in her Introduction to Hack Wit (with Ron Horn, 2016). They say it about writing translated from other cultures and writing with any whiff of formal consciousness never mind stretch… Have a pdf;

.As a Fn to the above remarks about Carson and Clare, Adrian Searle scratched away at it nicely here; ‘In a book accompanying the Hack Wit drawings, Canadian poet and classicist Ann Carson writes a text that at one point collides the English “peasant poet” John Clare and Marilyn Monroe. “They were both peasants,” Carson writes, “both lit by an all-consuming genius and woe … They might have knocked each other’s socks off … instead each died alone.” Carson’s collisions mirror Horn’s, and she splices what seem to be Horn’s words (it is hard to know, exactly) with her own. Carson takes Horn’s art somewhere it hadn’t been before. Which I guess is our job too.’ I asked her about the relations to Clare -shared or otherwise?- at the launch in fact. It was an awkward question because it revealed that Horn was not familiar with Clare, any association was in my own mind, but Carson beamed an eloquent reply, rolling terms from Clare’s work around with invested glee… So, back around to Kelman…

.