Elias Khoury’s Yalo was one of my stones stepped in 2009 [see Categories] and it’s on the long-list for The Independent’s Foreign Fiction Prize, announced here. Competition is stiff, needless to say, but I hope it wins.

I posted a link to the interview-based piece I did around the seminal publication in English of Bab al shams [Gate Of the Sun] in 2005 -the first of its kind in English- and now post it below. Gate of the Sun is a monumental work of fiction; a brilliant creative achievement which is both important and highly accessible. That is, it’s so compelling that there’s no excuse for not realising the necessity of reading it.

I posted a link to the interview-based piece I did around the seminal publication in English of Bab al shams [Gate Of the Sun] in 2005 -the first of its kind in English- and now post it below. Gate of the Sun is a monumental work of fiction; a brilliant creative achievement which is both important and highly accessible. That is, it’s so compelling that there’s no excuse for not realising the necessity of reading it.

In the US Archipelago Books is promising two new Khoury titles; a novel called White Masks in 2010 and another novel As Though She Were Sleeping in 2011. There are already two more works of fiction published in the US by university presses. I’m looking forward to the day when his critical writing becomes available to the English-speaking world.

Wherever you start with Khoury [an earlier novel, Little Mountain Collins Harvill 1990 is out of print] you’ll be hungry for more.

Elias Khoury: Myth and memory in the Middle East

Lebanese writer Elias Khoury is one of the leading lights of Arab literature. Guy Mannes-Abbott meets him

Friday, 18 November 2005

Elias Khoury is the kind of writer who wins the Nobel Prize for literature to sneers from the English-speaking world. When the Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz was greeted in this way in 1989, the late scholar and activist Edward Said remarked sagely that “Arabic is by far the least known and the most grudgingly regarded” of major world literatures. At the same time, Said pointed to the future, celebrating the promising achievements of Khoury – a “brilliant figure” – and Mahmoud Darwish: a Lebanese and a Palestinian writer respectively.

The word “brilliant” is etched across Khoury’s new novel, Gate of the Sun (Harvill Secker, £17.99) and on my mind when we meet in London for lunch. His reputation as a novelist, critic, commentator, editor and academic with real political commitment is formidable. Khoury came to prominence in Lebanon – and therefore the Arab world – in the mid-1970s. Still in his twenties, he was working in the Palestine Research Centre, editing the literary pages of its journal and writing his second novel, Little Mountain, which re-worked his experiences in the Lebanese civil war of 1975-1990 almost as they happened.

I feel more Beiruti. If you are a Beiruti, you are an Arab. You are open to all types of cultures, and to innovating in the Arabic culture at the same time.

“It’s meaningless!” he thunders, when I ask him what it means to be Lebanese. Then, speaking rapidly, he develops a characteristic response which ends with a modified repetition of the phrase. In between, he sketches a history of Lebanon’s many civil wars since the 19th century, describes similarities in dialect and cuisine between Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, and asserts that “I feel more Beiruti. If you are a Beiruti, you are an Arab. You are open to all types of cultures, and to innovating in the Arabic culture at the same time. You are in the Lebanese dilemmas and you are so near to Palestine”. So you feel “that the Palestinian tragedy is part of your life.”

By this he means sheer physical proximity – “It’s a matter of 100 kilometres” – but also that he has grown up with the Palestinian refugees who arrived in 1948, the year of his birth. All of this is the subject of the epic Gate of the Sun, which has already been cheered in Arabic, Hebrew and French editions during the seven years it took to arrive in this elegant English translation by Humphrey Davies.

Gate of the Sun, or Bab al Shams, is an attempt to render the Palestinian nakba – or “catastrophe” – of 1948 and its tortuous aftermath.

Gate of the Sun, or Bab al Shams, is an attempt to render the Palestinian nakba – or “catastrophe” – of 1948 and its tortuous aftermath. Specifically, it contains the stories and lives of people whose ancestral villages in Galilee, now in northern Israel, were “wiped out of existence”, forcing them into desperate flight by land and sea to Lebanon.

“Actually,” says Khoury, “I was writing a story about Galilee, because it’s in-between” and home to many Palestinian writers, including Darwish. “I was not writing a history of Palestine. Of course, many ask why it was a Lebanese not a Palestinian who wrote this story. I really don’t know. What I know is from the experience of the Palestinians I worked with,” he explains.

“actually this is something unbelievable.”

The nakba of 1948 was “a shame, a total defeat; it’s a disaster, a real personal disaster. There are stories here about the woman who left her child, about a woman who killed her child. So it’s not easy to talk about. The Palestinians did not realise, and if they realised they did not believe that this could happen, because actually this is something unbelievable.”

Khoury had the initial impulse to turn stories he heard in refugee camps into a memorial narrative in the 1970s. He spent much of the 1980s gathering “thousands of stories” before writing this extraordinarily accomplished novel. Gate of the Sun is essentially a love story set in a world turned upside down. It involves a dying fighter called Yunis and his wife Naheeleh, an internal refugee in Galilee, whose relationship forms during stolen visits across the border to a cave renamed Bab al Shams. The cave is “a house, and a village, and a country”, and “the only bit of Palestinian territory that’s been liberated”. It produces a “secret nation”: a family of seven children who have borne four more Yunises by the end of the book.

The cave is “a house, and a village, and a country”, and “the only bit of Palestinian territory that’s been liberated”.

However, this is no parable. For Khoury, “Yunis, of course, is a hero. He used to go to Galilee, he used to cross the borders… but in the end we discover that he was nothing, that Naheeleh was this whole story; her relationship with the children, and how she actually defended life. In the refugee camps I met hundreds of women like Naheeleh. Then it’s no more a metaphor. It’s very realistic.”

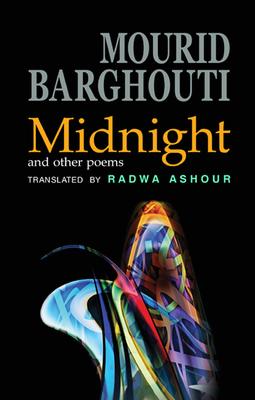

This reality is the “revolution of actual work carried out by our mothers”, which the poet Mourid Barghouti articulates so well

This reality is the “revolution of actual work carried out by our mothers”, which the poet Mourid Barghouti articulates so well in his memoir I Saw Ramallah. It is “realised every day, without fuss and without theorising”.

Khoury’s story of love and survival is told by Khaleel, an untrained “doctor” at a redundant hospital in Shatila refugee camp. Shatila was the site of a notorious massacre in 1982, overseen by an Israeli army commanded by Ariel Sharon. During the months that Khaleel attends to Yunis’s lifeless body, he stitches together his honorary father’s stories in order to bring him out of coma. Gradually, Khaleel’s own story emerges: of his love for a female fighter called Shams, and his experience of the camp massacre.

If this evokes the Thousand and One Nights, in which Scheherazade tells stories to keep herself alive, it’s the structure and act of telling that are important. Edward Said praised Khoury’s innovations in Little Mountain and the author takes the compliment, but says that “when I came to write Little Mountain, I discovered that real experimentation is not intellectual”. Instead, you have to “go deep to your own experience”.

These years involved “a very deep engagement about what is justice, what is a human being and what is life”.

In 1967, aged 19, Khoury travelled alone to Amman to join the Palestinian resistance after Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. In 1970 he finished his studies in Paris before writing his fictional debut, a nouveau roman. In 1975 he fought for revolutionary change in Lebanon, his disillusionment captured elegantly by Little Mountain. These years involved “a very deep engagement about what is justice, what is a human being and what is life”.

“I don’t think there is any story we live from the beginning to the end,” he says.

It is this experimenting with life, combined with such testing experience of it, that makes his writing less “experimental” in the literary sense than naturalistic. Crucially, he developed a faith in oral narratives; encompassing both the colloquial forms used in telling a story, and the non-classical type of Arabic that such stories are told in. “I don’t think there is any story we live from the beginning to the end,” he says. In this novel, “the structure is oral telling – openness. That is, you begin a story, you enter another story, and then you come back”.

In the novel, Khaleel complains about fugitive “snatches” of story that he’s struggling to remember and narrate. He blames the influence of tarab, the ecstasy generated by the rhythms of Arabic music and – by extension – poetry for the sidelining of descriptive skills. Khoury elaborates: “It’s repetitive, but every time you repeat, you change. Also in prose you create music, repeating the same story three, four, five times, and every time it’s a very slight difference. This is the Thousand and One Nights, this is the musicality of the oral and this is tarab.”

One of the results is that it produces “suspense from a totally different perspective. If you want to know what will happen to Yunis, he will die, so close the book and go home; but it’s another type of suspense.” It is this rhythmic accumulation of story that makes Gate of the Sun so unexpectedly compelling. It’s also this democratic form of telling which has enabled Khoury to approach the subject; to piece together fragments into a masterfully executed novel. The resulting mosaic of suggestive truths complicates any simple metaphorical reading while returning over and over again to discrete realities.

The Israeli project is to make a myth into reality. This is the problem.

“Reality,” he summarises, “can become metaphor or a myth. But a myth, if it will become a reality, it’s the most savage thing in the world. The Israeli project is to make a myth into reality. This is the problem.”

Khoury’s iteration of inconvenient realities is rigorously ethical. It is there in his responsibility towards Jewish history as well as to Palestinian dispossession, and in his novel’s investigation of love’s work. It informs his efforts to modernise Arabic by means of colloquial speech, and his commitment to grassroots democratic movements in Lebanon and Syria.

Khoury’s experience of life has generated a sophisticated optimism. He takes the long view, having resettled in the ancestral home in Beirut from which he was driven in the 1970s. He is both worldly and warm, a man of heart as well as passionate intellect. Nothing is off-limits and he answers every question fully even though we have, literally, eaten into preparation time for an evening reading. Before parting, though, I must ask the author of Gate of the Sun about the theory that “to narrate is to return”.

These paradoxes and “pleasures” find potent resolution in Gate of the Sun. It’s a novel that will outlive us.

“No, I think that to narrate is to reconstruct, to appropriate but,” he breaks into a story from one of his novels before resuming, “one of the biggest, er, pleasures of the Palestinians was to regain your name, to be Palestinians. And once you regain your name – and I think this is narration, to regain the name – then you prepare yourself to go: that is, to create a Palestine, not to return to a Palestine which was.” These paradoxes and “pleasures” find potent resolution in Gate of the Sun. It’s a novel that will outlive us.

Biography: Elias Khoury

Elias Khoury was born in Lebanon in 1948, to an Orthodox Christian family in the East Beirut district known as Little Mountain. As a sociology undergraduate, he volunteered for Fatah, the military wing of the Palestinian revolution. During the 1970s he worked in PLO organisations in Beirut, and helped found the journal al-Karmel with the poet Mahmoud Darwish. He speaks Arabic, French, English, Syriac and “a little Hebrew”. Author of 11 novels, four non-fiction books and three plays, he also scripted a film of Gate of the Sun. The novel is published by Harvill Secker this month. Khoury is now an editor with the Lebanese newspaper An-Nahar and Global Distinguished Professor at New York University. He lives with his wife in his great-grandfather’s house on Little Mountain.

![Slavoj Zizek 1998 [Photo Mykel Nicolaou]](https://notesfromafruitstore.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/slavoj-zizek-1998-photo-mykel-nicolaou.jpg?w=848&h=641)