When Tom Trevor presented a retrospective of the willfully wide ranging works of the late Angus Fairhurst at the ‘new’ Arnolfini in Bristol I expected much journalistic mythologising as well as critical celebration or at least engagement. Aside from the curator’s herald and despite the publication of a first monograph to accompany the show, Angus -a quintessentially English radical of the visual arts- remains woefully under-recognised and his work awaits critical ‘rediscovery’ at some predictably safe distance of time.

Anticipating the wake-like opening and its celebratory aftermath I arrived early enough to spend an hour alone in the galleries. Back home, laid up with a torn calf muscle in the first snowy days of February 09, I was moved to a first and wrote this conventional review of the show. I submitted it to ‘a national newspaper’ who said they had it covered, failing to mention what the reviewer had covered it with.

I’m posting my piece as it was; a first modest attempt at some of the truth…

AngusFairhurstAtArnolfiniGuide2009

Done.

By Guy Mannes-Abbott

In life, Angus Fairhurst was casually misrepresented as a kind of avant-garde jester in the YBA pack. The error was symptomatic of a nagging lack of recognition before his very public suicide on March 29th 2008. A joke requires a punch line to satisfy commonsensical and Freudian definitions. This first Retrospective at Bristol’s Arnolfini bristles with Fairhurst’s witty resistance to formulaic closure and clarifies a very particular seriousness of purpose.

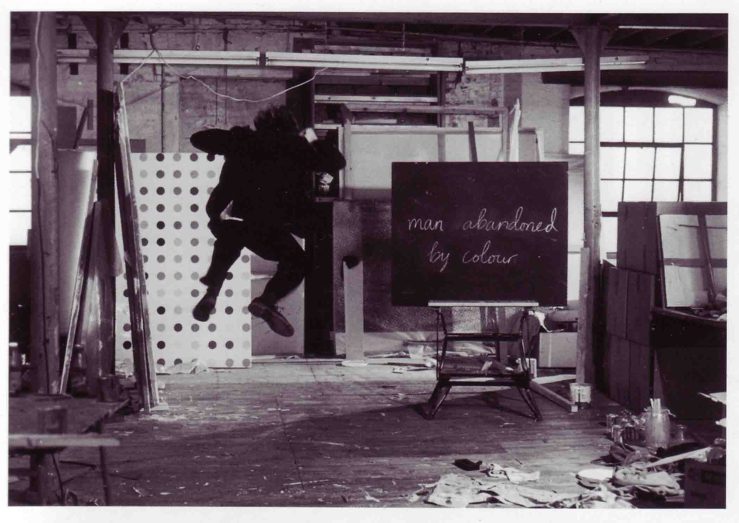

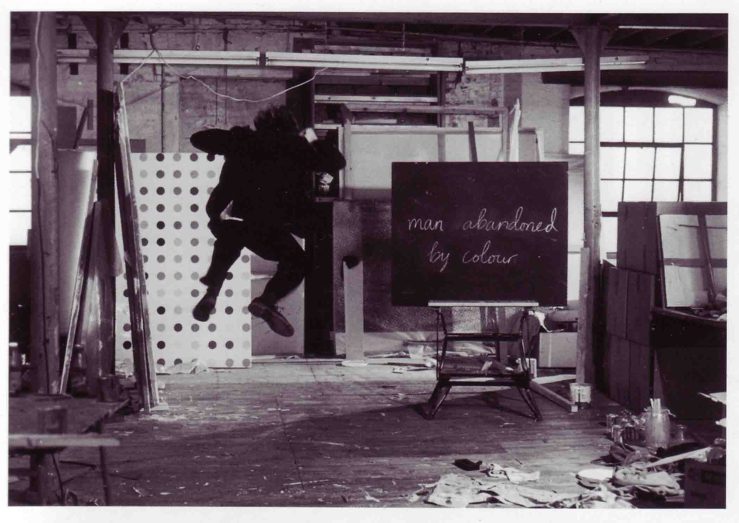

The Arnolfini has drawn together a show full both in its formal range; paint, sculpture, film, photography, pencil drawing, sound and collage, and the sheer strength of the work across several galleries. From this fullness, and for the first time, a narrative emerges to what was a very disparate, narrative-defying practice. All retrospectives leave things out. Here, much of the earliest work is missing. So let me demonstrate how one notable absence, a photograph called Man Abandoned by Colour [1992], rehearses much of this exhibition’s ‘story’.

Man Abandoned by Colour 1992 Angus Fairhurst

Man Abandoned shows the artist, back to camera, jumping like an ape beside a free standing blackboard on which the title is written in Magritte’s hand [from The Treachery of Images]. Hints of silent-era comedy compete with art historical reference and a foregrounding of ‘background’; the slightly abject studio stacked with work. This particular studio was shared with Damien Hirst; an early spot painting leans behind an iron pillar and ladder. So there you have Angus Fairhurst. Except that there’s more: the building and artist are gone, that ‘background’ has become art historical, the image has gained new dimensions. Between this and Fairhurst’s final series of paintings is a paradigm shift and circular arc: a spiralling of potential.

This exhibition begins and ends with Undone [2004]; a large bronze banana, skinless, black-painted, “edition one of three”. Upstairs is a latex banana skin, along with massive bronze gorillas and mirroring water-holes, gorilla suits and a performance video of the artist shedding it, as well as fine drawings of Fairhurst encountering himself, the self, and subjectivity itself, via the ape. I’ve long been indifferent to the sculptures, whose ‘point’ is optimised in cartoon drawings on paper, but here they earn their place. Even the primary-colour wall paper overprinting of wintery forests, also from In-a-Gadda-da-Vida [group show with Hirst and Sarah Lucas at the Tate in 2004], gains from this context. Images of a tree bared of, and potential with, life recur in collages and paintings right up to a final chilling sculptural relic; Lessons in Darkness [2008].

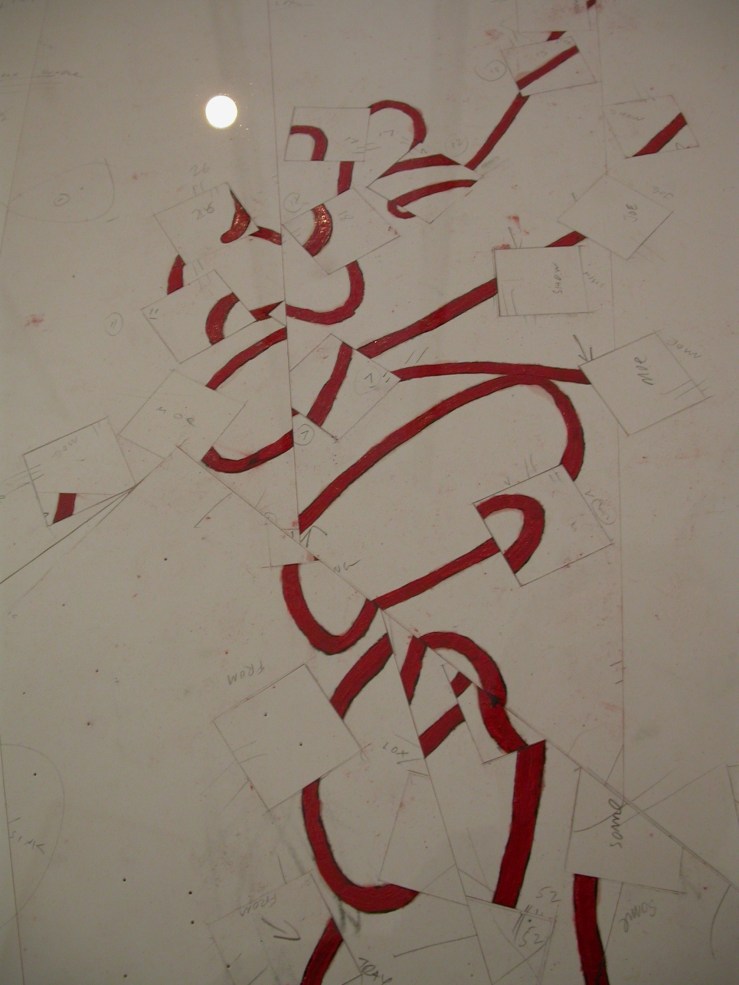

Fairhurst’s radically suggestive collages are central to this show and his achievement. His earliest works blew up printed images until their coloured dots became unreadable. Here, collages of billboard posters import a recognisable urban scale then explode with dimensional depth and multitudes. Look closely at them and you find a Blue Peter, art-for-all aesthetic at work; cheap materials and great simplicity turned to lasting effect. Take Billboard, Everything but the Outline Blacked-In [2003]; a naked Sophie Dahl reclining in the famous ad for Opium perfume. Look closely at the figure shrouded in black paint and you appreciate the distinction between a gesture of blacking-out and Fairhurst’s exquisite blacking-in. Now the model’s outline, created by brushstrokes, resembles solar light on the horizon, old-for-new days.

Elsewhere are many small collages of magazine pages or posters, their words, figures, and subjective space, removed, cut-out and layered. Apparent simplicity of intent is enriched, again, by manifest precision. On larger works like Seven billboards [2004] these carved masses build like paint on a late Lucien Freud canvas. Incisions open on other rooms, days and vistas through spectacular space towards a speculative architecture of our time. In the 19th Century, modern ‘man’ descended into crowds, today that ‘crowd’ runs through us just as it does through these cut-outs or, more exactly, cut-ins of our promiscuous hyper-space.

Through these portals we arrive at Fairhurst’s most lasting achievement; the series of paintings begun in 2007 and shown at Sadie Coles’ gallery in 2008. It was on the last day of that exhibition that Fairhurst made his very considered final act. Inevitably it threatens to cast a romantic, mythologising light on these last works, but they don’t need help of that kind.

Fairhurst’s earliest work adopted Eva Hesse’s clothes tags to insert into and screen out his or Hirst’s canvases and cabinets. He was still bewitched by her titling into the mid-noughties, fretting over word chains; Unwork, Unseen, Unwit etc. These final works are a departure even at the level of their titling; Schopfun, Epha, Eenp, Gree. The latter three are half a metre square, some of the smallest works on show. Schopfun is a more transitional work, a larger canvas combining collage with paint rendered by hand and silkscreen. Like Epha, it’s a close up, centring on a painting-in of the kind of models he removed from advertising. Here figures are highly ambiguous; on display and not.

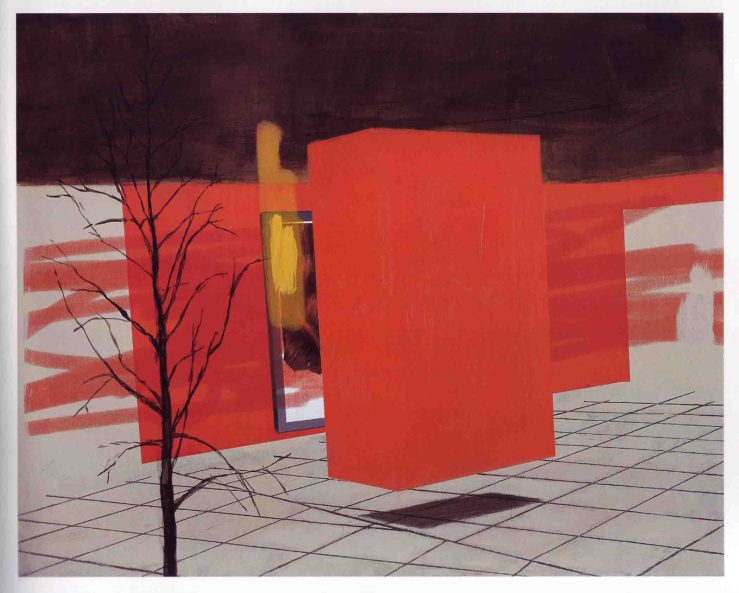

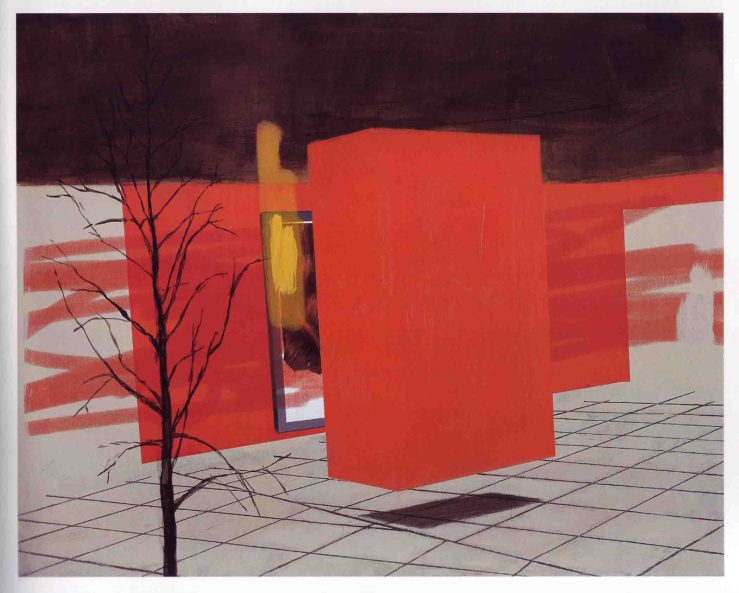

Eenp 2008 Angus Fairhurst

Yet it’s Eenp and Gree that make the starkest claim on our attention, I think. Much of Fairhurst’s work is condensed in these paintings, not least that photograph; Man Abandoned by Colour. There is warm colour here but nothing seductive about these canvases. There is no way out of them. Nowhere to be if you find your way in. They render a no-place, in which recognisable gallery or domestic walls float impossibly above broken grids of flooring, perspectives laid down and lost. One immediate association is with the interiors of David Lynch’s recent films; spaces in time, contingent, truly uncanny. On one wall an image hangs, partially obliterated by marks within and without the frame -of that image and the potential ‘built space’. Marks overwritten by computer-originated spraying-out which resembles graffiti; a form of spraying-in. Here Fairhurst renders a generative threshold: within and without, interior and exterior, place and no-place, being and not.

Gree 2008 Angus Fairhurst

Eenp contains a tree, growing into the image, massive pillars float high in it beneath cosmological space. Gree contains an image, or smudged figure, painted out in the hand of Francis Bacon. It’s another art historical reference, half obliterated, and to an artist collected, incidentally, by Damien Hirst. A spiral of light years links Gree to Man Abandoned by Colour. These final paintings engage what Giorgio Agamben means by radical potential. Far removed from the “heroic pathos of negation”, with these works Fairhurst was “dwelling in the abyss of potentiality”.

So there is pleasure and satisfaction in this retrospective despite its tragic lure. These potent, difficult, mesmerising, abysmal, yes, as well as bleakly solitary last works celebrate making, creation, art. Angus Fairhurst had reached a significant stage in his work and as an artist. In life he often practised sleights of hand dressed as consumable art-gestures. In death his art subverts all such gestures with its resonant singularity. This is work that speaks clearly to us and though we may not listen, even now, we will remember it.